New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you sign up for the Local Running Drop.

A decade ago, Flora Duffy nearly quit the sport. Now she’s short course’s most dominant athlete on- and off-road with four ITU world titles— two in draft-legal tri, two in cross—and four XTERRA World Championship titles to her name. Kelly O’Mara gets an inside look at the charitable phenom’s long journey to success.

I’m in a cab from the Bermuda airport, on my way to meet ITU world champ and four-time XTERRA world champ Flora Duffy in her hometown, and my cab driver has some thoughts. “If she wins [at the Olympics] in Tokyo, she’ll be the most famous Bermudan ever,” he argues.

Apparently, she’s currently in contention with a historic soccer player and maybe a sailor from the 1950s. Or so says my cab driver, who dives into the intricacies of ITU competition, unprompted.

But this was in January, back before she won gold at the Commonwealth Games, before she was awarded an Order of the British Empire, and before she won the first-ever ITU World Triathlon Series race in Bermuda in front of the biggest crowd most Bermudans had ever seen. “It made the America’s Cup look small,” recalls Neil de Ste. Croix, the head of the Bermuda youth tri club. “Everyone was chanting her name.” When I meet Duffy in January, passing joggers cheer for her, and waiters want her autograph. But now, after the Bermuda WTS race in April? Now, it’s at another level. De Ste. Croix sends me an email from a friend: Her niece dressed up as Duffy for a school project. The prompt was: “Dress as something that makes you proud to be Bermudan.”

Even if Duffy doesn’t win at the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo—and odds are she will—she’s already the first woman from Bermuda to win a medal at the Commonwealth Games and the first person ever to win four XTERRA world titles. She was the most successful triathlete in 2017, by far, losing just one race since her surprise win at the 2016 ITU Grand Final and topping the prize money list last year. Yet, after dropping out at the Beijing Olympics 10 years ago, the girl from a tiny island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean almost quit the sport completely.

Made in Bermuda

Made in Bermuda

I am here to tell you: Flora Duffy does 40-second side planks timed with an iPhone just like everyone else. We ride three hours at a moderate pace, to one end of the hilly stone-walled island and back. (A random guy riding a rusted bike with a basket jumps on the back of our pack, and she just laughs. “That’s a very Bermuda thing to happen,” she says.) We run tempo repeats on a flat trail—or, rather, I jog and she runs four minutes on, 90 seconds recovery, and then 6 x 2:40 on, with 80 seconds recovery. She pads in bare feet around the Bermuda National Training Centre, which is the fancy name for a small basement gym with boxes, barbells, and basic weight machines. The security guard takes a selfie with her.

Yes, this is an easy week for her, but these are basic standard workouts everyone does. The only difference is in the video the Specialized marketing team takes, which shows her hamstring curls and planks and ball crunches are just a little sharper and more focused than mine. She’s concentrating just a little harder.

Duffy doesn’t come back to Bermuda that much anymore. She primarily splits her time now between Stellenbosch, South Africa, where her husband and former XTERRA pro, Dan Hugo, is from, and Boulder, Colorado, where she went to college. But it was in Bermuda where she originally learned the skills that would make her a world champion decades later.

“It’s all in the timing,” says her dad, Charlie, who works in the insurance industry, as do her two brothers. It just so happened there was a kids’ triathlon group when she was young. It just so happened ITU was getting its start when she was a junior racing. It just so happened she learned hard lessons over the years, slowly progressing bit by bit. Maybe it’s just in the timing.

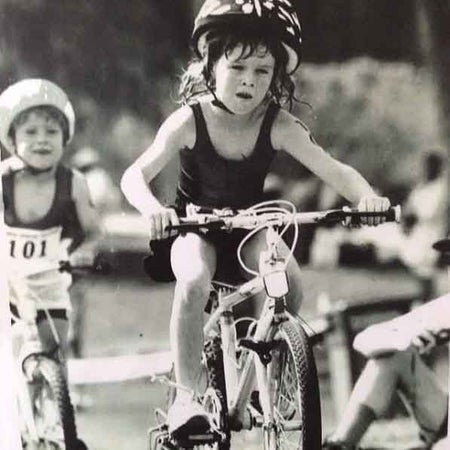

When Duffy was 7 or 8, there was a new kids’ triathlon program in Bermuda, called Tri-Hedz. De Ste. Croix started the group with three others to bring triathlon to the local kids. They’d meet on Saturdays at Clearwater Beach.

Fifty kids would be out there picking up cones on the bike and practicing transitions. Mostly, though, they were having fun. “Always, the focus was on fun,” says de Ste. Croix. Duffy wasn’t much different from the other Bermuda kids then. She’d grown up biking around the island. (Cars in Bermuda are limited to one per household.) She ran in school and swam with the local swim club, just like all her friends in Tri-Hedz did.

There were competitions all summer around the island, and once per year they would travel to Chicago for a big race—all 50 kids, with their parents and coaches, in matching t-shirts.

There must be something to this island triathlon program, though. Bermudan Tyler Butterfield, who took fifth at Kona in 2015, came out of the same era as Duffy. And this year Bermuda, population 65,000, took fifth in the mixed relay at the Commonwealth Games.

There is an abnormal number of good triathletes for such a small place. “It’s definitely weird that Bermuda’s tiny and has this tri club that’s thriving,” Duffy says.

At first, the kids’ summer tri camp might have just been for fun, but Duffy likes to win. At that annual race in Chicago, she’d battle fiercely with a set of American sisters. Most of her friends eventually moved on, but she didn’t. “It was light fun, but I was quite an intense kid,” she says. She trained with older youth and it was clear early on that she hated to lose, says de Ste. Croix. “She still has the same look on her face when she races.”

At first, the kids’ summer tri camp might have just been for fun, but Duffy likes to win. At that annual race in Chicago, she’d battle fiercely with a set of American sisters. Most of her friends eventually moved on, but she didn’t. “It was light fun, but I was quite an intense kid,” she says. She trained with older youth and it was clear early on that she hated to lose, says de Ste. Croix. “She still has the same look on her face when she races.”

In 1996 and 1997, a few years into summer tri camp, there was a World Cup race held in Bermuda. Watching it, Duffy decided she could do this. “When people asked me, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ I’d say, ‘I want to be a pro triathlete, world champion, and gold medalist.’ And they’d look at me like, ‘Oh shit, I think this little girl really means it.’”

To make that happen, when she was 16, she decided she needed to go to Mt. Kelly, a boarding school in England known for its swim program and its small four-person triathlon squad. Due to a limited number of higher education options on the island and Bermuda’s

strong ties to Britain, many young Bermudans leave for boarding school or college, but not all of them pick a school focused on sports. “It was a decisive moment,” Duffy says—and it took her triathlon to a new level.

English boarding school is different than Bermuda, though. It’s not island life anymore. It’s not primarily about having fun. “It was posh to me,” she remembers.

Duffy got stronger, but she also got messed up. “On the one hand, I was getting faster,” she says. She took eighth at the Commonwealth Games and second at the World Juniors race.

She started racking up top-10s at ITU World Cups. “But on the other hand, it was a very destructive path to get there.” At first, it started as just trying to eat healthier, “but I’m a rather intense person,” she says, and soon she was cutting out so many calories her body couldn’t handle it. She had an eating disorder; she was getting injured. Her body was so calorie-deprived, she even started putting on weight; her body was trying to compensate as she struggled to find a balance.

“It was a really, really rough time for me. I hit rock bottom in Beijing,” she says. “My body had had enough.” At the Beijing Olympics, she DNF’d.

Dejected, beaten up, and worn out, she went back to Bermuda, intent on doing nothing related to triathlon. She worked at a local tourist shop and bummed around the island. She was done as a serious athlete.

Steps to Becoming a World Champion

I am intent on visiting the school Duffy attended through her freshman year of high school to see if I can find some secret in the building. The pool at the Warwick Academy has been renamed the Flora Duffy Swimming Facility, but it’s just a 25-meter pool, on the side of a pastel colonial building, like most of the buildings in Bermuda, with stone arches and large staircases—except in a less intimidating way than the oldest school in the Western Hemisphere sounds like it should be. It’s a Saturday morning when I bike by, and there are kids playing soccer and parents driving minivans.

She came back here last year to dedicate the pool and give a speech. This year, she set up The Flora Fund with the Bermuda Community Foundation to support other young athletes—and there are a lot of young athletes showing up at Tri-Hedz wanting to be just like her. It’s no surprise Bermudans can swim; they’re surrounded by water and temperate climates.

What’s harder to understand are the group rides that meet every week to hammer around 20-square miles.

After Beijing, Duffy spent months on the island, unsure what to do next. “It was really hard to watch,” says her dad, to see her struggling untethered.

That October, in 2008, she applied to the University of Colorado, Boulder, without ever having been to that state; she’d known people who had gone there and liked the combo of education and outdoor opportunities. Plus, the mountains sounded like a nice change. She started school in January, already 21 and older than most of the freshmen on campus. She didn’t have a solid plan, “I just knew I had to do something,” she says.

In Boulder, “no one cared who you were,” she says. Everyone there did some kind of activity, so she started biking with the cycling team. It was competitive, but not unhealthy competitive.

She studied sociology and joined a sorority, Alpha Ki Omega. If she wasn’t a serious triathlete anymore, why not be a fun college student instead? It lasted three months. “It was a life epiphany,” she says. “I thought, ‘This is not me, who am I trying to be? You are a triathlete.’”

That’s where the other Boulder advantage comes in. “She called me in January 2009 at some point and said, ‘I think I met you on a plane,’” says Neal Henderson, who would wind up coaching her for nine years. They had met briefly on a flight to Beijing, where he was coaching Taylor Phinney at the Olympics. She wanted to work with him now that she was in Boulder—at first, just in cycling.

She started out just riding local races. (Though, let’s be clear: In her version of having fun, she took fifth at collegiate nationals in the omnium and was named to the College All-Star team.) But soon she was asking Henderson if she could come to some swim sessions with his other athletes. When she wanted to start running, it was only 20 minutes at a time, no structure. “It took months,” he says, before she built up to running a few times a week.

“The biggest thing was providing an environment where she had a lot more choice and a lot less pressure,” Henderson recalls. He wanted her to train next to his other world-class athletes and to see there was a way to be the best without breaking yourself.

In 2010, she completed her first triathlon since the Olympics, the Hy-Vee World Cup and came in top 20. There were ups and downs after that—fifth at one race, 40th at the next. “It took a long time for me to actually be good again,” Duffy says, but it was all with a different perspective: “I love it, and this is what I want to do,” she says.

To most people, Duffy was a solid ITU racer, but not dominant. It wasn’t until the end of 2016, when she beat recent gold medalist Gwen Jorgensen at the ITU Grand Final in Cozumel that the triathlon world really took notice. What had changed? I asked her parents. They had one word: Dan.

Dan Hugo and Duffy met in Boulder back in 2010 “and she didn’t pay me any attention,” he joked.

But they started hanging out and ran in the same training groups. By 2013, they were dating. Because they were spending time together, she started riding her mountain bike more. She raced an XTERRA and “got annihilated,” she says, but it qualified her to the world championships. And she got enough better by then—practice, practice, practice—that she took third at the XTERRA World Championship. “Her learning curve seems really steep,” Hugo says. The technical practice helped, but it was also just a happy, fun time.

She graduated, and it was a make-or-break moment to commit full-time. The couple went to Stellenbosch to train in the winter, and Hugo urged her to take her natural potential to the next step.

“He wrote me this letter,” she says. It was titled, “Flora’s Steps to Being a Multiple World Champion,” and it was just that: a list of things to do to become world class. “It’s comical now how much of it was elementary,” he says. Things like get enough sleep, eat properly, have a massage once per week. But his point was: You could be the best, if you dot your i’s and cross your t’s. Don’t be so intense that you get an eating disorder, but be a little more focused than a college kid who’s just doing this part-time.

In fact, one of the bigger arguments the couple had back then was Hugo begging her to get regular massages, and she just couldn’t see the point. “It baffled me,” he says.

The list sunk in, though, and she started working her way through it.

“It made a pretty profound impact on me,” she says. “Someone had thought through these things and thought I could be world class.”

In 2014, she won the XTERRA World Championship. Yes, the mountain biking helped her technical skills, but the win helped her confidence. “I realized, ‘You can compete at this level,’” she says. The next race after that, the first ITU WTS race of 2015, in Abu Dhabi, she grabbed her very first WTS podium.

Know Thyself

If you’re drinking wine with her, Duffy does not seem like an intense person. “She’s very much not classic Type A,” Hugo says. She can turn it on and off. The last night in Bermuda, we go to a fancy restaurant on the water.

She orders the tempura jumbo shrimp and a plate of sushi, and then we put her in charge of ordering wine. Turns out, if you’re a world champion, you’re not really a heavy drinker. She laughs about trying to decipher wine descriptions, recommends Dave Chappelle Netflix specials, and talks U.S. politics. At one point, she explains the difference between a jail and a prison.

She tells a story how after a workout once, in Boulder, she ate two giant hamburgers. Can you imagine that? I tell her yes, I can.

The gist of the story is that she doesn’t love red meat, but she’s learned she has to eat some since she was anemic back in 2013. She’s relearned her running form after stress fractures. She’s learned how to bounce back after crashing at the London Olympics. She missed the beginning of 2017 because of a stress reaction in her hip. She missed several races this year because of a foot injury and ultimately was not able to race enough to try to defend her world title. She’s learned lessons over and over again, bit by bit.

“It seems like this whole six-, eight-year journey to get to where I am now,” she says.

When she was still building back up after graduating, there was a WTS race in Cape Town where she led most of the bike, but then her nerve failed her and she wound up finishing third. The next race, in Stockholm, she went all in, came off the bike with a 30-second lead and won her first WTS. We’re all born with a certain amount of potential, and then have to choose how to maximize it. If Duffy had quit before now, says Henderson, she never would have known how good she could be. “There’s something kind of beautiful in that,” says Hugo, of the journey. She’s built a small team around her now, of running specialists and cycling coaches, but she mostly travels to races by herself or with Hugo. Some days it seems like she can’t lose, and some days it seems like it’s just a question of staying healthy one workout at a time.

She was supposed to race the mountain bike at the Commonwealth Games, alongside triathlon, but she made the calculated decision not to. It was too high a risk—she’s not that good a mountain biker (not compared to the best in the world)—with too much to lose. “She’s very calculated,” Hugo says. It’s finding the space in between the desire to simply race as hard as she can and making the smartest decision that’s helped her get to the top.

She studies tape now, before and after her big races—of the race the year before, of the course, of the other girls—to figure out where the gaps could form.

Is that a common thing other people do? I ask. “I don’t know if it’s a thing people do,” Duffy says. “It’s a thing I do.”

If you watch a lot of WTS races, it can seem sometimes like she just rides as hard as she can, takes all the risks to get as much advantage as she can on technical courses. She must be fearless, have some inner drive the rest of us don’t. But that’s not the case. She’s not particularly risk-seeking. She tried riding one of the World Cup mountain bike courses in South Africa and bailed out of a few of the trickiest lines. Riding as hard as she can in a race is a choice she makes based on understanding her strengths (and weaknesses), and analyzing the courses.

“It’s what I need to do to be on the podium, so I just do it,” she says. It took her years and a lot of mistakes to learn to believe in herself, and to know that if she rides as hard as she can at the right moment, she can be the best in the world.

*The Flora Fund*

In May, Duffy announced she’d created a fund with the Bermuda Community Foundation to provide local athletes with funding for expenses including equipment, travel, training

fees, event registration, and coaching. “This is a small start,” she says. “But I hope to grow the foundation into a meaningful and sustainable community asset that positively impacts the youth of Bermuda.”